In October, Washington announced some of the strongest export controls to date, requiring licenses for companies that export chips to China using American tools or software, regardless of where in the world they are made.

The new measures also prevent US citizens and green card holders from working for certain Chinese chip companies, blocking a key pipeline of US talent to China, which is sure to affect the development of high-end semiconductors.

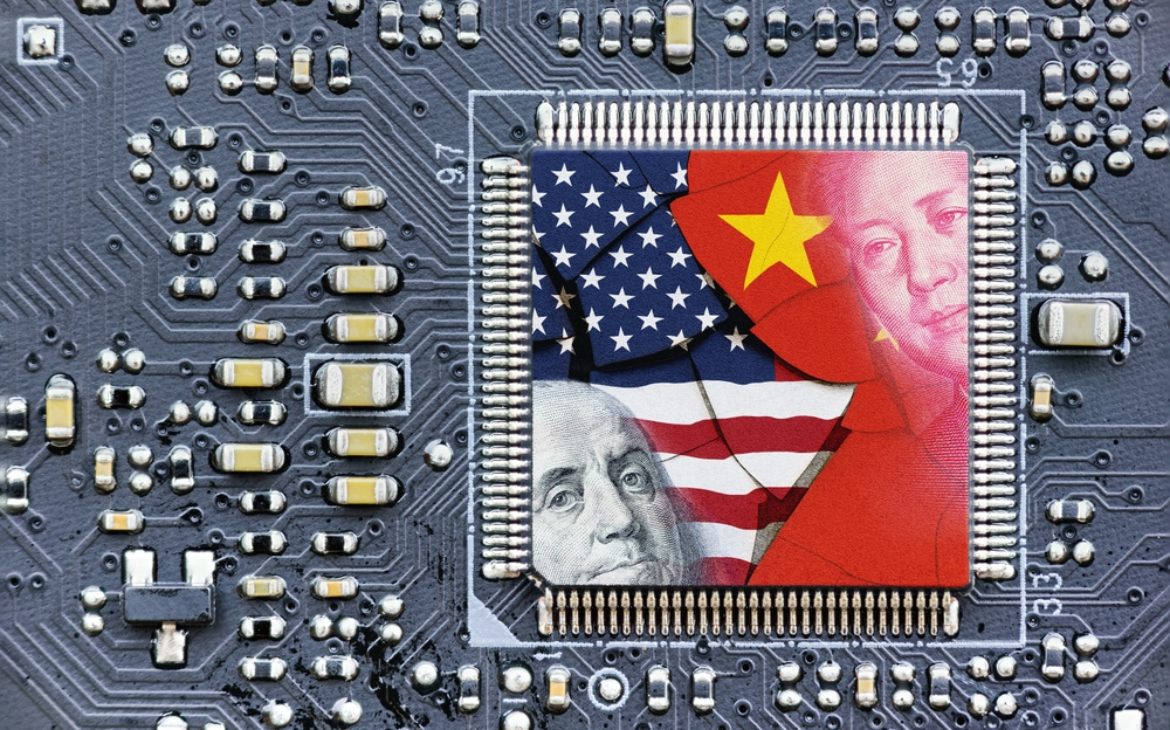

Advanced chips are used to power supercomputers, artificial intelligence, and military hardware.

The US claims that China’s use of this technology poses a threat to national security.

Alan Estevez, undersecretary at the US Department of Commerce, announced the rules, saying he intended to ensure the US does everything it can to prevent China from acquiring “sensitive technologies with military applications”.

On the other hand, China called the controls “technology terrorism”.

Asian chip-making countries – such as Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea – have expressed concern about how this battle is affecting the global supply chain.

Three significant events have recently marked the ongoing chip conflict.

The Biden administration added 36 more Chinese companies, including major chipmaker YMTC, to Washington’s “entity list”.

This means that US companies will need government approval to sell certain technologies to them, and that approval is challenging to obtain.

Afterwards, China filed a complaint against the US with the World Trade Organization (WTO) over its export controls on semiconductors and other related technology.

This is the first WTO case Beijing has brought against the US since President Biden took office in January 2021.

In its WTO filing, China alleged that the US was abusing export controls to maintain “its leadership in the science, technology, engineering, and manufacturing sectors”, adding that US measures threatened “the stability of the global industrial supply chains”.

The US responded that the WTO was “not an appropriate forum” to address national security concerns.

US Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Export Administration Thea Kendler said that “US national security interests require that we act decisively to deny access to advanced technologies.”

The complaint details that the United States has imposed export restrictions on approximately 2,800 Chinese products, but only 1,800 of them were permitted under international trade rules. The Americans have 60 days to try to resolve the issue. Otherwise, China will be allowed to call for a panel to review its case.

Japan and the Netherlands could also impose export controls on China – limiting their companies’ ability to sell advanced products in the Chinese market.

On Monday, White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said the US had held talks with the two major suppliers of chip-making equipment about adopting similar controls on Beijing.

The US controls are not only aimed at chipmakers, but also affect manufacturers of chipmaking equipment.

Large companies in Japan or the Netherlands could thus lose a large and lucrative customer for their high-end machines.

Peter Wennink, CEO of Dutch chip equipment maker ASML Holding NV, questions whether the Netherlands should limit exports to China. In response to US pressure, the Dutch government already halted the sale of ASML’s most advanced lithography machines to China in 2019, so Wennink claims his company has already made enough sacrifices.

Chipmakers are also under pressure to make more advanced chips to support new products.

For example, Apple’s new notebook computer will contain 3-nanometer chips from the leading Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. To put it in perspective: human hair measures approximately 50,000 to 100,000 nanometers.

Analysts say the US controls could set China further back among other chip producing countries, though Beijing has openly said it wants to prioritize semiconductor production and become a superpower in the sector.

The US has already managed to significantly isolate China’s chip industry, even if the latest measures are not as extensive as those announced in October.